Klicka på bilden för en större version på svenska!

Also in English.

An act of aggression in 1135

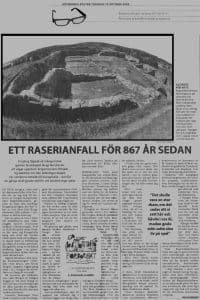

The ruins of the old medieval fortress of Ragnhildsholmen on the beach at Nordre alv are now completely desolate. Long ago a terrible battle was fought at Ragnhildholmen former fortress around Kungahalla. Today the traces of Kungahälla fortress has mostly disappeared.

Early one morning, as the morning fogs are rising from Nordre alv, I travel to the ruins of the fortress of Kungahälla, near those of Ragnhildsholmen. I had been following the winding Kongahälla Road where it turns off to Säve from Kungälvsleden (E6) ever so near The castle of Bohus.

Let us travel through the winds of time to the events depicted by the Icelandish historian Snorre Sturlasson in the chronicles of Heimskringla in 1135. At the other side of Nordre Älv from where I am, loomed Kungahälla town and fortress. It was the sixth largest town in Norway and its southernmost outpost with its population of only a few hundred people. Kungahälla fortress is an earthwork castel in a politically contested area. People were often fighting fierecly over this area with sword and fire.

Sigurd Joralafar (Sigurd who went to Jerusalem), the Norwegian Crusader king (1103-1130) had this earthwork erected sometime about 1111. The king’s intent was probably to strengthen and glorify his power.

The king’s household guards (Swedish ”hirdmän”) were patrolling the walls. The fortress probably consists of wood with parts of it in stone or clay. Around the fortress, there is a ditch, maybe even a moat. This was to make it harder for a would-be aggressor.

Inside the fortress, there is both a church and a royal demesne house (kungsgård) for Guttorm Haraldsson, the local bailiff. The townspeople are living in longhouses. Oak poles and half-timbering in between held the walls erect.

The place is very much one of a kind. Most people who live here seem to be quite wealthy. These magnates are probably receiving their revenues from locally executing the will of the king. The floors are made of wood in the houses of the rich and are otherwise made of burned soil.

The streets and alleys are full of goats, which would otherwise mostly be found in the traditional parts of Norway. But sheep, cows, pigs and hen are also roaming the alleys. Trash would have been thrown diectly out in the middle of the street to spread its perfume. Where the streets are mushy with water, they are covered by gabled bridges (wooden walking bridges). In addition, the wealthier neighbourhoods have stone walkways in the middle of the alleys. The commoners or horses and wagons hade to use the mud walkways surrounding the ones in stone.

We are now at the day of the feast of St. Lawrence (August, 10) in 1135 A.D. In the harbour, there are nine ships that have arrived from the east. Maybe they had been trading at Birka or with the Russians in Kiev.

Kungahälla would not be experiencing the grace of God this year. A malign and faraway guest does now interrupt the priest, Andreas Brunsson, in his holy works. The Wendish lord Rettibur does threateningly approach with his navy probably to burn and loot. The men in the church now haste down to their town properties. There they arm themselves for battle and draw their bows and arrows.

The sounds of iron against iron soon echo through the village below the locla fortress. Both the visiting merchants and the local men join the battle against the bandits, these horrible, Slavic heathens from around nowaday northern Poland and Germany.

The heroes of Kungahälla are pressing the robberers as good as they can. In the peak of the battle, the defendents shot their arrows against the hostile ships from the harbour. The power of the thrusts of the men of Kungahäölla manage to sink many of the enemy ships.

A request for help is sent off to the surrounding villages and farmsteads. When Ölve Big-Mouth does hear of the surpirse attack, he stretches out for his shield, helmet and big axe saying:

— We shall rise, good yeomen, and seize our arms. It would be a great shame if it were to be said that we were sitting here drinking lots a beer while good men were putting their lives at risk in the village for our safety. One or two heathens ought to fall before me before I perish.

Ölve hastens to the very centre of the battle. Here eight of the heathens immediately attack him. Ölve manages to wield his axe so that it breaks the neck and the jaws of one of the heathens. But in the end, God is not on the side of his own in this skirmish.

As the defendants beging to be lacking in arrows and spears, the townspeople have to resort to staffs to fight with. Not even the small chip of the holy cross that Sigurd Jorsalafar had donated to the Kastalachurch is of very much aid. It does not even help that the local priest takes part in the fighting.

After many hard fights, the Norwegians have to surrender themselves and the Holy Cross to the mercy of the infidel.

Nowadays, these events have faded from the memory of men. The heathen religion of the Wends is now being disputed by the scientists. The Wends did probably not attack Kungahälla so much for its riches on this day.

Some scientis dispute the importance of Kungahälla as a place of trade, since the remains of bartering are so few. The town is on the other hand full of clay pottery from Germany, France and England. These are signs of longway contacts.

The goal of the attacking Wends was most likely to destroy the local power structure of the Norwegian King. This local fortress was an important part of this power structure. For the Norwegian king was an ally of the Danes who were enemeies of the Wends.

Inside of the fortress, there is an interesting finding of a Slavic piece of women’s jewelry. This might be a sign of parellell peaceful contatcs between Kungahälla and the Wends.

Many Wendish princes were allied with Germans or Danes against other Slavic, German or Danish lords. Many scientiests are disputing the Wendish hostility versus Christianity.

From the crest of Ragnhildsholmen, I get a good overview of the waters where the medieval trading vessels hade arrived after having been cruising between the lands of the Norwegians, the Danes, and the people of Västra Götaland.

In our days, almost nothing remain of the fortress of Kungahälla, but its successor fortress does. The ruins on Ragnhildsholmen did at least fire off my imagination and ought to be an exciting place for kids to play at. The Göteborgs-Posten reporter sat down here to listen to the dramatic wings of history.